Radiofrequency generators have been used in medicine for around a century, and RF is widely used in

a multitude of disciplines; in fact, an estimated four out of every five surgical procedures now employ

radiofrequency energy in some form. Some of its most promising newer applications are based on the

principle of thermocoagulation, in which heat is used to destroy tissue—but as with many things, that description only scratches the sur-

face of what is really going on.

For example, the phrase“heat is used to destroy tissue”could apply to electrocautery as well, but the

two procedures differ in several key respects. In electrocautery, thegenerated energy is used to heat a

metal wire, which the practitioner then applies directly to the tissue, causing damage similar to

third degree burns. In radiofrequency ablation, on the other hand, the electrode remains cool, because the heat used for thermocoagulation is generated in the tissue itself.

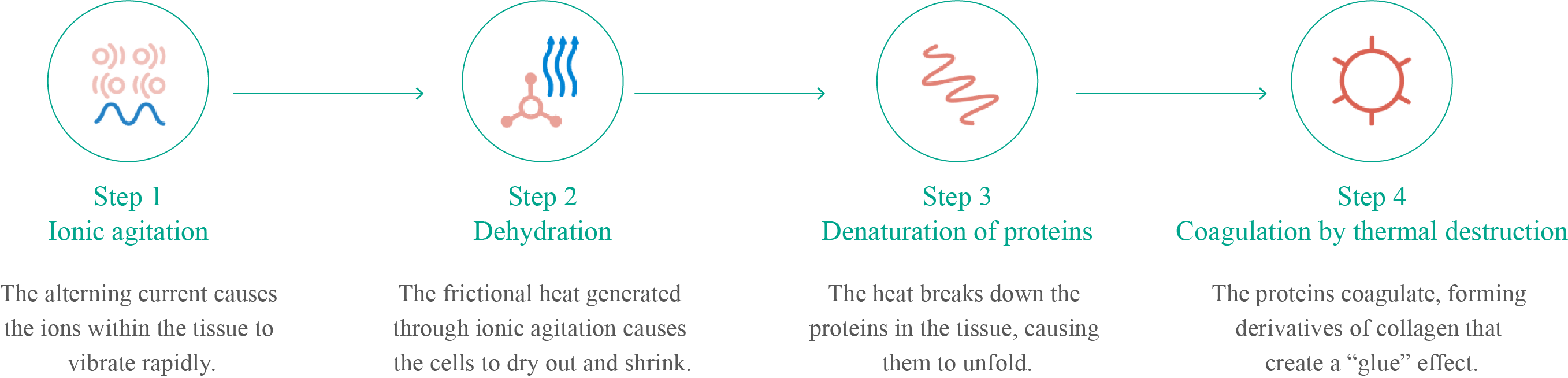

How? Monopolar RF generators create a closed electrical loop: from the generator to the patient’s

body, to the electrosurgical pad (if used), to the generator. This electrical current is painless for the

patient because the frequency is too high to trigger depolarisation of nerve membranes, so the nerves

never fire. The high-frequency current agitates the ions within the tissue as they attempt to follow the

alternating current’s changes in direction—which happen so fast that the ions vibrate without moving.

Such vibration creates significant frictional heat in the immediate vicinity of the electrode, but the

effect decreases dramatically with distance: a 2 mm Rafaelo® electrode, for example, has a thermal

radius of just 3 mm. This represents a major advantage over electrocautery, which typically has a sig-

nificantly greater range of heat spread

(and thus greater potential for inadvertent tissue damage).